The NYT Deal Professor notes: “J. Crew, Michelle Obama’s sometime clothing retailer, is yet  another struggling private equity buyout. J. Crew’s owners, TPG Capital and Leonard Green & Partners, are stuck, tied to the bargain they struck with the company’s chief executive, Millard S. Drexler. Call it the ‘great man’ problem.” In other words, is the strategic asset a single individual or a set of organizational routines that are robust to key individuals leaving? In this case, J. Crew investors and the board were bound to go with CEO Millard S. Drexler’s recommendations and take the company private. Current struggles suggest limitations to this great man’s capabilities. Indeed, in Leonard Barton’s terms, he is looking more like a core rigidity. This has become a recurring theme. We have explored (in the toolbox) the implications of this for Steve Jobs at Apple but more recently for Jony Ive as Apple’s product development guru. This mini-case may encourage a discussion of strategic human capital, capabilities, organizational routines, and how these relate to corporate governance. Do such key individuals reduce or enhance sustained competitive advantage? Then, along the lines of my own work (Coff, 1999), there is the question of implications for rent appropriation. Clearly Drexler has done well on that front…

another struggling private equity buyout. J. Crew’s owners, TPG Capital and Leonard Green & Partners, are stuck, tied to the bargain they struck with the company’s chief executive, Millard S. Drexler. Call it the ‘great man’ problem.” In other words, is the strategic asset a single individual or a set of organizational routines that are robust to key individuals leaving? In this case, J. Crew investors and the board were bound to go with CEO Millard S. Drexler’s recommendations and take the company private. Current struggles suggest limitations to this great man’s capabilities. Indeed, in Leonard Barton’s terms, he is looking more like a core rigidity. This has become a recurring theme. We have explored (in the toolbox) the implications of this for Steve Jobs at Apple but more recently for Jony Ive as Apple’s product development guru. This mini-case may encourage a discussion of strategic human capital, capabilities, organizational routines, and how these relate to corporate governance. Do such key individuals reduce or enhance sustained competitive advantage? Then, along the lines of my own work (Coff, 1999), there is the question of implications for rent appropriation. Clearly Drexler has done well on that front…

Contributed by Russ Coff

Here is a simple exercise to demonstrate competitive advantage on the first day of class. Hold up a crisp $20 bill and ask “Who wants this?” When people look puzzled, ask, “I mean, who really wants this?” and then “Does anyone want this?” Continue this way (repeating this in different ways) until someone actually gets up, walks over, and takes the $20 from your hand. Then the discussion focuses on why this particular person got the money. How did their motivation differ? Did they have different information or perception of the opportunity? Did they have a positional advantage based on where they were sitting? Other personal attributes (e.g., entrepreneurial)? The main question, then, is why do some people/firms perform better than others? This simple exercise gets at the nexus of perceived opportunity, position, resources, and other factors that operate both at the individual and firm level. Note that instructors should tell the class not to share this with other students. However, if you do have a student who has heard about the exercise (and grabs the money), asymmetric information about an opportunity is certainly one aspect of the discussion. The following “

Here is a simple exercise to demonstrate competitive advantage on the first day of class. Hold up a crisp $20 bill and ask “Who wants this?” When people look puzzled, ask, “I mean, who really wants this?” and then “Does anyone want this?” Continue this way (repeating this in different ways) until someone actually gets up, walks over, and takes the $20 from your hand. Then the discussion focuses on why this particular person got the money. How did their motivation differ? Did they have different information or perception of the opportunity? Did they have a positional advantage based on where they were sitting? Other personal attributes (e.g., entrepreneurial)? The main question, then, is why do some people/firms perform better than others? This simple exercise gets at the nexus of perceived opportunity, position, resources, and other factors that operate both at the individual and firm level. Note that instructors should tell the class not to share this with other students. However, if you do have a student who has heard about the exercise (and grabs the money), asymmetric information about an opportunity is certainly one aspect of the discussion. The following “ Economic bubbles reflect irrational escalation but there is always an element of underlying rationality. This classic exercise,

Economic bubbles reflect irrational escalation but there is always an element of underlying rationality. This classic exercise,  Abercrombie & Fitch is struggling (

Abercrombie & Fitch is struggling ( Rejection, almost inevitable, doesn’t deter them. The rest of us kill inventive ideas before we even test them because we fear rejection.

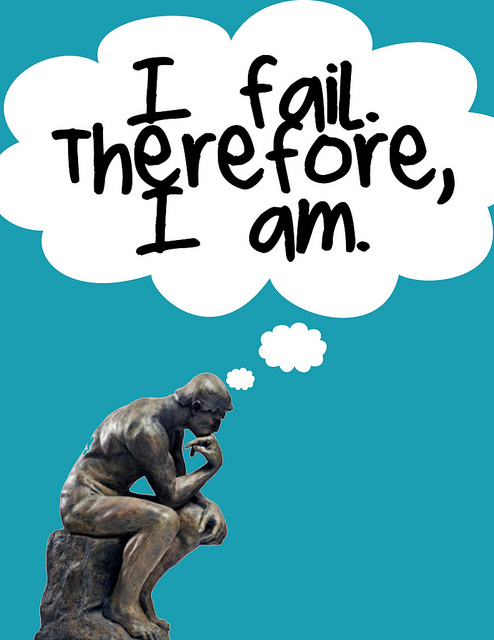

Rejection, almost inevitable, doesn’t deter them. The rest of us kill inventive ideas before we even test them because we fear rejection.  An emerging literature focuses on learning from failures — both in terms of entrepreneurship and strategy more broadly. For some recent examples, see studies by

An emerging literature focuses on learning from failures — both in terms of entrepreneurship and strategy more broadly. For some recent examples, see studies by  MicroTech is a negotiation over the terms to transfer a technology between 2 divisions of a company to take advantage of a market opportunity. Sub-optimal agreements (money left on the table) represent transaction costs and inefficiencies that must be overcome in order to create corporate value. There are two roles (Gant and Coleman). One division, Household Appliances (HA), has developed a new technology that has value if sold outside of the company. However, the division does not have a charter to sell chips. In order to take advantage, the technology must be transferred to the Chips & components (CC) division. In the process, about 20-40% of the potential value is typically left on the table. The discussion focuses on how to align objectives and achieve cooperation across divisions. It turns out that such cooperation is hard to achieve in a competitive culture. How, then, can the firm create a cooperative culture? This, it turns out, may be a VRIO resource…

MicroTech is a negotiation over the terms to transfer a technology between 2 divisions of a company to take advantage of a market opportunity. Sub-optimal agreements (money left on the table) represent transaction costs and inefficiencies that must be overcome in order to create corporate value. There are two roles (Gant and Coleman). One division, Household Appliances (HA), has developed a new technology that has value if sold outside of the company. However, the division does not have a charter to sell chips. In order to take advantage, the technology must be transferred to the Chips & components (CC) division. In the process, about 20-40% of the potential value is typically left on the table. The discussion focuses on how to align objectives and achieve cooperation across divisions. It turns out that such cooperation is hard to achieve in a competitive culture. How, then, can the firm create a cooperative culture? This, it turns out, may be a VRIO resource… They started Justin.tv to broadcast their lives, but soon discovered that people really wanted to watch gaming.

They started Justin.tv to broadcast their lives, but soon discovered that people really wanted to watch gaming.  The “Vision Thing” exercise is designed to help students distinguish the activities of leaders and managers in a fun and engaging manner. The exercise involves creating a three-tiered hierarchical structure. One person is the CEO, another is the manager, and a third is the employee. The CEO prepares a vision statement in advance and works with the manager to determine how to translate the vision to a tangible “product” using the toy construction set. The manager then guides the employee on building the “product.” The process is iterative in nature—the manager can communicate with the CEO and employee as often as necessary. But there is a finite amount of time available to implement the vision. Once the exercise is complete the team comes together to examine how close the team came to implementing the CEO’s vision. The learning objectives are:

The “Vision Thing” exercise is designed to help students distinguish the activities of leaders and managers in a fun and engaging manner. The exercise involves creating a three-tiered hierarchical structure. One person is the CEO, another is the manager, and a third is the employee. The CEO prepares a vision statement in advance and works with the manager to determine how to translate the vision to a tangible “product” using the toy construction set. The manager then guides the employee on building the “product.” The process is iterative in nature—the manager can communicate with the CEO and employee as often as necessary. But there is a finite amount of time available to implement the vision. Once the exercise is complete the team comes together to examine how close the team came to implementing the CEO’s vision. The learning objectives are: especially for executive audiences. While there are large gaps in our understanding of personality and leadership, research does provide several pointers that can help assess who would be a good organizational leader in different contexts.

especially for executive audiences. While there are large gaps in our understanding of personality and leadership, research does provide several pointers that can help assess who would be a good organizational leader in different contexts.  here are lots of cases, exercises, & simulations dealing with making strategic decisions, but few that deal with execution. Since implementation is a major hurdle for achieving a successful strategy, this can leave an important gap in the traditional strategy course.

here are lots of cases, exercises, & simulations dealing with making strategic decisions, but few that deal with execution. Since implementation is a major hurdle for achieving a successful strategy, this can leave an important gap in the traditional strategy course.  Glad to have that cleared up. Years later, mission statements are still a key focus in the practice of strategy despite being almost ignored in the academic literature. One could ignore this in teaching strategy (many do) or one might discuss when mission statements are a grand waste of time and when they may prove to be useful. Automated mission statement generators help to make this point. While there are several good ones,

Glad to have that cleared up. Years later, mission statements are still a key focus in the practice of strategy despite being almost ignored in the academic literature. One could ignore this in teaching strategy (many do) or one might discuss when mission statements are a grand waste of time and when they may prove to be useful. Automated mission statement generators help to make this point. While there are several good ones,