Alliances may be disrupted for reasons beyond partners’ control, ranging from pandemics to cyber attacks. They then look to the contract for a way forward. When obligations are not met, contracts focus attention on blame and penalties for the breach. Force majeure clauses may void a contract without penalties but they are typically applied narrowly, if at all (weather-related events, etc.). So, the parties must assess blame, assign penalties, and void the existing contract before finding a way forward even if a disruption could not have been anticipated or prevented. Economic recovery from the pandemic depends on many firms addressing this difficult challenge.

This negotiation exercise, conducted in a session at the SMS Milan conference, drives that point home. The context is a UK-based office equipment company (SmartTech) and their alliance with an Italian chip manufacturer (ChipComm). Italy was closed down by the pandemic while the UK remained open and the supplier was unable to meet obligations. The parties must determine if ChipComm is culpable and if so, what penalties apply. Then, they need to identify how they might revise the contract to move forward. Of course, building trust to move forward after assessing penalties is no easy task.

The exercise is straightforward in terms of the timing. We describe the setting and assign roles in class. Then they have 5 minutes to read the 2-page roles. We then pair them with someone who has the opposite role and give them 15 minutes to negotiate. They can then enter their contracts into a Google form which summarizes the contracts for class discussion. Here are the materials: SmartTech role, ChipComm role, Sample form for students to enter contracts.

This leads to a rich discussion of when contracts are harder to reboot (degree of trust, fairness/sharing losses, attribution of blame, contract language regarding penalties or bonuses, nature/extent of the disruption, etc.). For example, students may compare the pandemic context to a disruption caused by a less pervasive factor, such as a ransomware attack. Prior specific investments make both parties more committed to continuing the relationship – perhaps even if the specific assets are no longer needed. Then, the question is how to gain trust when the contract has failed, and who to involve in the process (lawyer cat may be less helpful here…).

Contributed by Libby Weber and Russ Coff

The

The  I like to start the semester with a “ripped from the headlines” case. This is especially helpful if some of one’s cases are older. This semester, Zoom is a great alternative. The current

I like to start the semester with a “ripped from the headlines” case. This is especially helpful if some of one’s cases are older. This semester, Zoom is a great alternative. The current

How can we make online courses more interactive? Often people create videos of their PPT lectures as the basis of an online course. We know we can do better. It turns out that negotiation exercises can work surprisingly well online. My

How can we make online courses more interactive? Often people create videos of their PPT lectures as the basis of an online course. We know we can do better. It turns out that negotiation exercises can work surprisingly well online. My  Firms often make errors in selecting governance forms and the scope of the firm. This is one common reason firms must undergo painful periodic restructuring programs. If only managers could frame these problems more effectively and identify the key factors to make more informed decisions — in short, a primer on Transaction Cost Economics (TCE). Brian Silverman provides just that tool in a

Firms often make errors in selecting governance forms and the scope of the firm. This is one common reason firms must undergo painful periodic restructuring programs. If only managers could frame these problems more effectively and identify the key factors to make more informed decisions — in short, a primer on Transaction Cost Economics (TCE). Brian Silverman provides just that tool in a  Much of the news focuses on how hard businesses have been hit by the pandemic. However, strategy is about finding opportunities and adapting in a dynamic environment. Let’s not forget to focus on inspirational examples along these lines. Send students on a scavenger hunt (like the

Much of the news focuses on how hard businesses have been hit by the pandemic. However, strategy is about finding opportunities and adapting in a dynamic environment. Let’s not forget to focus on inspirational examples along these lines. Send students on a scavenger hunt (like the  I have taught during numerous crises (various wars, 911, 2008 crash, etc.) and always regretted missing opportunities to bring the events into the classroom. So how can we encourage our students to think strategically about the COVID crisis? Here are a few ideas for discussion or team projects (but

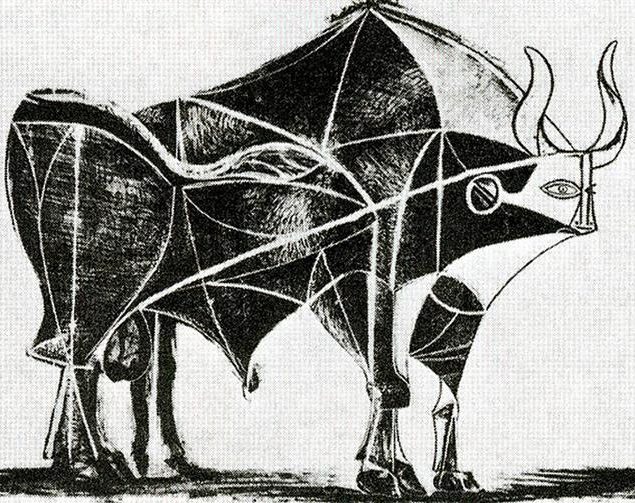

I have taught during numerous crises (various wars, 911, 2008 crash, etc.) and always regretted missing opportunities to bring the events into the classroom. So how can we encourage our students to think strategically about the COVID crisis? Here are a few ideas for discussion or team projects (but  Theory is, by definition, a simplification of reality. A useful theory is parsimonious in that it reflects the most important details of the context and allows for reasonably accurate predictions (see a

Theory is, by definition, a simplification of reality. A useful theory is parsimonious in that it reflects the most important details of the context and allows for reasonably accurate predictions (see a

Human capital is often considered to be a critical component of valuable capabilities. However, it is intimately tied to value capture in that one might anticipate that those who have valuable and rare skills might also be in a position to appropriate rent. Is it a competitive advantage if the resulting value does not flow to shareholders? The following survey gets at this question and may spur interesting discussion among academics and students alike.

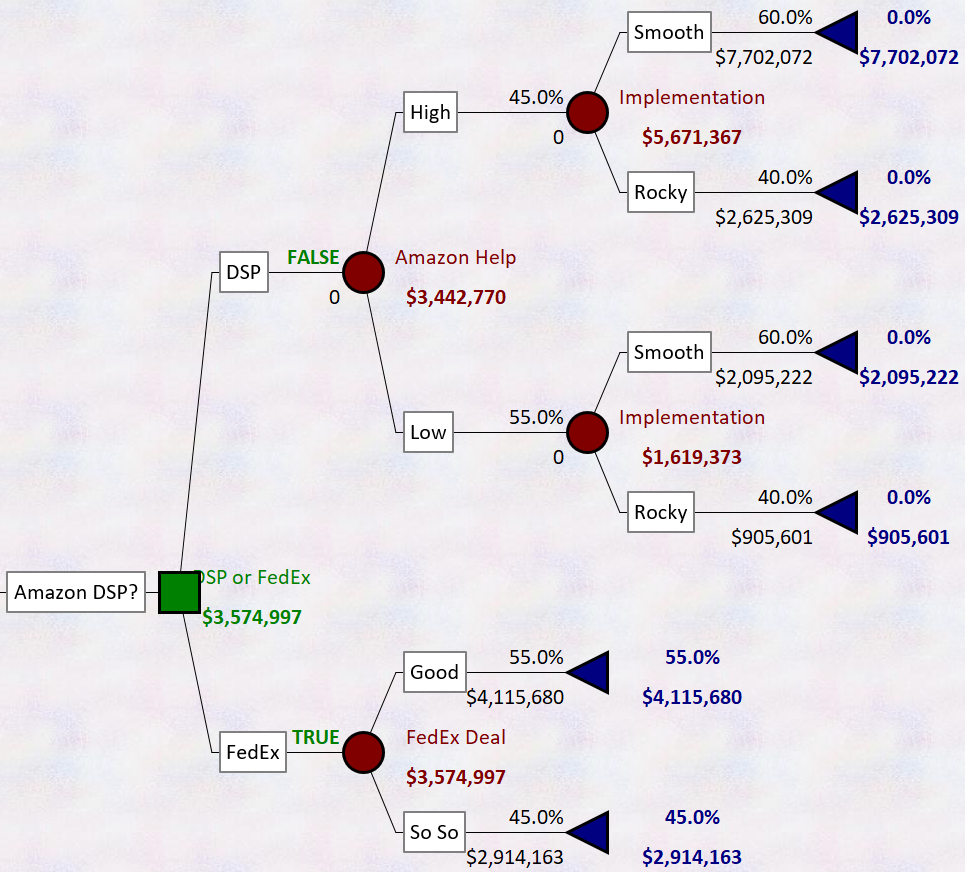

Human capital is often considered to be a critical component of valuable capabilities. However, it is intimately tied to value capture in that one might anticipate that those who have valuable and rare skills might also be in a position to appropriate rent. Is it a competitive advantage if the resulting value does not flow to shareholders? The following survey gets at this question and may spur interesting discussion among academics and students alike. Amazon is encouraging employee spinouts. They are offering employees $10,000 plus 3 months salary to quit and form entrepreneurial ventures in their

Amazon is encouraging employee spinouts. They are offering employees $10,000 plus 3 months salary to quit and form entrepreneurial ventures in their  Team projects are quite common in strategy classes. While the topic of team effectiveness is usually more central for organizational behavior courses, it is essential for organizational effectiveness … and team projects. While you may not want to allocate a lot of time and resources to the topic, you may want to get teams off to a good start so you don’t have to address dysfunctions later in the semester. One reason things may go south is the team’s desire for a “fast and enthusiastic start.” A bias for action can sometimes sabotage collaborative efforts. That well-meaning call to action — “let’s get this done!” – can result in a “sloppy start.”

Team projects are quite common in strategy classes. While the topic of team effectiveness is usually more central for organizational behavior courses, it is essential for organizational effectiveness … and team projects. While you may not want to allocate a lot of time and resources to the topic, you may want to get teams off to a good start so you don’t have to address dysfunctions later in the semester. One reason things may go south is the team’s desire for a “fast and enthusiastic start.” A bias for action can sometimes sabotage collaborative efforts. That well-meaning call to action — “let’s get this done!” – can result in a “sloppy start.” This 45-minute exercise can be used in a range of management courses and works well in almost any size class. Students are divided into two groups (managers and workers) that must cooperate to produce a re-organization (a simple seating chart). However, managers discover that workers are reluctant to move and about 90% of classes fail to achieve the task. This generates a lively discussion on what is required to lead change, as well as on topics such as communication, trust, power, and motivation. I just ran this for the first time and, to my surprise, the students were successful. However, in the process, it was clear that there were moments of distrust within and between groups. A last person held out to see if he could appropriate more value. In the end, the management team gave up all value that was created. That is, employees appropriated all of the value and managers actually lost money in the exercise. It was quite successful and students thanked me for the experience. All of the details needed to run the exercise are in the article at the link above and it was easy to set up and run.

This 45-minute exercise can be used in a range of management courses and works well in almost any size class. Students are divided into two groups (managers and workers) that must cooperate to produce a re-organization (a simple seating chart). However, managers discover that workers are reluctant to move and about 90% of classes fail to achieve the task. This generates a lively discussion on what is required to lead change, as well as on topics such as communication, trust, power, and motivation. I just ran this for the first time and, to my surprise, the students were successful. However, in the process, it was clear that there were moments of distrust within and between groups. A last person held out to see if he could appropriate more value. In the end, the management team gave up all value that was created. That is, employees appropriated all of the value and managers actually lost money in the exercise. It was quite successful and students thanked me for the experience. All of the details needed to run the exercise are in the article at the link above and it was easy to set up and run.