Alliances may be disrupted for reasons beyond partners’ control, ranging from pandemics to cyber attacks. They then look to the contract for a way forward. When obligations are not met, contracts focus attention on blame and penalties for the breach. Force majeure clauses may void a contract without penalties but they are typically applied narrowly, if at all (weather-related events, etc.). So, the parties must assess blame, assign penalties, and void the existing contract before finding a way forward even if a disruption could not have been anticipated or prevented. Economic recovery from the pandemic depends on many firms addressing this difficult challenge.

This negotiation exercise, conducted in a session at the SMS Milan conference, drives that point home. The context is a UK-based office equipment company (SmartTech) and their alliance with an Italian chip manufacturer (ChipComm). Italy was closed down by the pandemic while the UK remained open and the supplier was unable to meet obligations. The parties must determine if ChipComm is culpable and if so, what penalties apply. Then, they need to identify how they might revise the contract to move forward. Of course, building trust to move forward after assessing penalties is no easy task.

The exercise is straightforward in terms of the timing. We describe the setting and assign roles in class. Then they have 5 minutes to read the 2-page roles. We then pair them with someone who has the opposite role and give them 15 minutes to negotiate. They can then enter their contracts into a Google form which summarizes the contracts for class discussion. Here are the materials: SmartTech role, ChipComm role, Sample form for students to enter contracts.

This leads to a rich discussion of when contracts are harder to reboot (degree of trust, fairness/sharing losses, attribution of blame, contract language regarding penalties or bonuses, nature/extent of the disruption, etc.). For example, students may compare the pandemic context to a disruption caused by a less pervasive factor, such as a ransomware attack. Prior specific investments make both parties more committed to continuing the relationship – perhaps even if the specific assets are no longer needed. Then, the question is how to gain trust when the contract has failed, and who to involve in the process (lawyer cat may be less helpful here…).

Contributed by Libby Weber and Russ Coff

How can we make online courses more interactive? Often people create videos of their PPT lectures as the basis of an online course. We know we can do better. It turns out that negotiation exercises can work surprisingly well online. My

How can we make online courses more interactive? Often people create videos of their PPT lectures as the basis of an online course. We know we can do better. It turns out that negotiation exercises can work surprisingly well online. My  Much of the news focuses on how hard businesses have been hit by the pandemic. However, strategy is about finding opportunities and adapting in a dynamic environment. Let’s not forget to focus on inspirational examples along these lines. Send students on a scavenger hunt (like the

Much of the news focuses on how hard businesses have been hit by the pandemic. However, strategy is about finding opportunities and adapting in a dynamic environment. Let’s not forget to focus on inspirational examples along these lines. Send students on a scavenger hunt (like the  Theory is, by definition, a simplification of reality. A useful theory is parsimonious in that it reflects the most important details of the context and allows for reasonably accurate predictions (see a

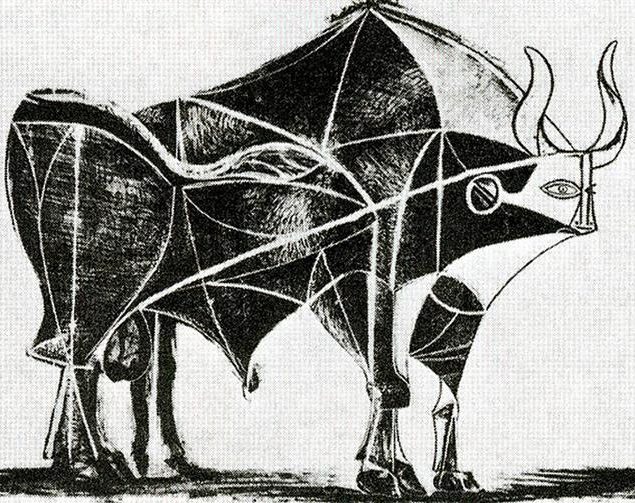

Theory is, by definition, a simplification of reality. A useful theory is parsimonious in that it reflects the most important details of the context and allows for reasonably accurate predictions (see a  Team projects are quite common in strategy classes. While the topic of team effectiveness is usually more central for organizational behavior courses, it is essential for organizational effectiveness … and team projects. While you may not want to allocate a lot of time and resources to the topic, you may want to get teams off to a good start so you don’t have to address dysfunctions later in the semester. One reason things may go south is the team’s desire for a “fast and enthusiastic start.” A bias for action can sometimes sabotage collaborative efforts. That well-meaning call to action — “let’s get this done!” – can result in a “sloppy start.”

Team projects are quite common in strategy classes. While the topic of team effectiveness is usually more central for organizational behavior courses, it is essential for organizational effectiveness … and team projects. While you may not want to allocate a lot of time and resources to the topic, you may want to get teams off to a good start so you don’t have to address dysfunctions later in the semester. One reason things may go south is the team’s desire for a “fast and enthusiastic start.” A bias for action can sometimes sabotage collaborative efforts. That well-meaning call to action — “let’s get this done!” – can result in a “sloppy start.” This 45-minute exercise can be used in a range of management courses and works well in almost any size class. Students are divided into two groups (managers and workers) that must cooperate to produce a re-organization (a simple seating chart). However, managers discover that workers are reluctant to move and about 90% of classes fail to achieve the task. This generates a lively discussion on what is required to lead change, as well as on topics such as communication, trust, power, and motivation. I just ran this for the first time and, to my surprise, the students were successful. However, in the process, it was clear that there were moments of distrust within and between groups. A last person held out to see if he could appropriate more value. In the end, the management team gave up all value that was created. That is, employees appropriated all of the value and managers actually lost money in the exercise. It was quite successful and students thanked me for the experience. All of the details needed to run the exercise are in the article at the link above and it was easy to set up and run.

This 45-minute exercise can be used in a range of management courses and works well in almost any size class. Students are divided into two groups (managers and workers) that must cooperate to produce a re-organization (a simple seating chart). However, managers discover that workers are reluctant to move and about 90% of classes fail to achieve the task. This generates a lively discussion on what is required to lead change, as well as on topics such as communication, trust, power, and motivation. I just ran this for the first time and, to my surprise, the students were successful. However, in the process, it was clear that there were moments of distrust within and between groups. A last person held out to see if he could appropriate more value. In the end, the management team gave up all value that was created. That is, employees appropriated all of the value and managers actually lost money in the exercise. It was quite successful and students thanked me for the experience. All of the details needed to run the exercise are in the article at the link above and it was easy to set up and run. The Alphabet Soup

The Alphabet Soup Strategy classes often give short shrift to managing change but this is where the rubber hits the road.

Strategy classes often give short shrift to managing change but this is where the rubber hits the road.  Generic strategies are easy enough to explain and students typically feel that they understand. But do they really? Could they develop and implement a sound strategy? Sometimes it’s worth a bit of additional hands-on experience to make sure the lessons stick. Probably the most important message is alignment — the need to design the organization and product to fit the strategy. In other words, to make the appropriate tradeoffs.

Generic strategies are easy enough to explain and students typically feel that they understand. But do they really? Could they develop and implement a sound strategy? Sometimes it’s worth a bit of additional hands-on experience to make sure the lessons stick. Probably the most important message is alignment — the need to design the organization and product to fit the strategy. In other words, to make the appropriate tradeoffs.  Entrepreneurship students often think they’ve found a “no brainer” idea – one that everyone “obviously” will want. We’ve all seen it before – an idea that is so good that it requires zero dollars for customer acquisition because word of mouth and social media will lead to infinite sales, virtually overnight.

Entrepreneurship students often think they’ve found a “no brainer” idea – one that everyone “obviously” will want. We’ve all seen it before – an idea that is so good that it requires zero dollars for customer acquisition because word of mouth and social media will lead to infinite sales, virtually overnight.

Strategies rarely work out as planned but somehow, students remain eternally hopeful that everything will go exactly as they expect. This experiential exercise allows students to “feel”

Strategies rarely work out as planned but somehow, students remain eternally hopeful that everything will go exactly as they expect. This experiential exercise allows students to “feel”  Inflate ball & sit on it. Ask 2 volunteers to inflate a heavy duty inflatable ball using a small air pump (one can buy these a sport store) and try to sit on it afterwards for a minute. While introducing the exercise, the instructor should keep the plug hidden in her/his pocket. Inflating the ball is amusing (both the volunteers and the audience). It is not easy or quick to inflate the ball.

Inflate ball & sit on it. Ask 2 volunteers to inflate a heavy duty inflatable ball using a small air pump (one can buy these a sport store) and try to sit on it afterwards for a minute. While introducing the exercise, the instructor should keep the plug hidden in her/his pocket. Inflating the ball is amusing (both the volunteers and the audience). It is not easy or quick to inflate the ball. takes the plug out admitting that she/he had it all the time. The class will laugh. It may be frustrating for the volunteers but then we begin the debrief and explain the reason for the deception in the exercise.

takes the plug out admitting that she/he had it all the time. The class will laugh. It may be frustrating for the volunteers but then we begin the debrief and explain the reason for the deception in the exercise. Are there cultural norms for telling the truth?

Are there cultural norms for telling the truth?  Here is a simple exercise to demonstrate competitive advantage on the first day of class. Hold up a crisp $20 bill and ask “Who wants this?” When people look puzzled, ask, “I mean, who really wants this?” and then “Does anyone want this?” Continue this way (repeating this in different ways) until someone actually gets up, walks over, and takes the $20 from your hand. Then the discussion focuses on why this particular person got the money. How did their motivation differ? Did they have different information or perception of the opportunity? Did they have a positional advantage based on where they were sitting? Other personal attributes (e.g., entrepreneurial)? The main question, then, is why do some people/firms perform better than others? This simple exercise gets at the nexus of perceived opportunity, position, resources, and other factors that operate both at the individual and firm level. Note that instructors should tell the class not to share this with other students. However, if you do have a student who has heard about the exercise (and grabs the money), asymmetric information about an opportunity is certainly one aspect of the discussion. The following “

Here is a simple exercise to demonstrate competitive advantage on the first day of class. Hold up a crisp $20 bill and ask “Who wants this?” When people look puzzled, ask, “I mean, who really wants this?” and then “Does anyone want this?” Continue this way (repeating this in different ways) until someone actually gets up, walks over, and takes the $20 from your hand. Then the discussion focuses on why this particular person got the money. How did their motivation differ? Did they have different information or perception of the opportunity? Did they have a positional advantage based on where they were sitting? Other personal attributes (e.g., entrepreneurial)? The main question, then, is why do some people/firms perform better than others? This simple exercise gets at the nexus of perceived opportunity, position, resources, and other factors that operate both at the individual and firm level. Note that instructors should tell the class not to share this with other students. However, if you do have a student who has heard about the exercise (and grabs the money), asymmetric information about an opportunity is certainly one aspect of the discussion. The following “ Economic bubbles reflect irrational escalation but there is always an element of underlying rationality. This classic exercise,

Economic bubbles reflect irrational escalation but there is always an element of underlying rationality. This classic exercise,  MicroTech is a negotiation over the terms to transfer a technology between 2 divisions of a company to take advantage of a market opportunity. Sub-optimal agreements (money left on the table) represent transaction costs and inefficiencies that must be overcome in order to create corporate value. There are two roles (Gant and Coleman). One division, Household Appliances (HA), has developed a new technology that has value if sold outside of the company. However, the division does not have a charter to sell chips. In order to take advantage, the technology must be transferred to the Chips & components (CC) division. In the process, about 20-40% of the potential value is typically left on the table. The discussion focuses on how to align objectives and achieve cooperation across divisions. It turns out that such cooperation is hard to achieve in a competitive culture. How, then, can the firm create a cooperative culture? This, it turns out, may be a VRIO resource…

MicroTech is a negotiation over the terms to transfer a technology between 2 divisions of a company to take advantage of a market opportunity. Sub-optimal agreements (money left on the table) represent transaction costs and inefficiencies that must be overcome in order to create corporate value. There are two roles (Gant and Coleman). One division, Household Appliances (HA), has developed a new technology that has value if sold outside of the company. However, the division does not have a charter to sell chips. In order to take advantage, the technology must be transferred to the Chips & components (CC) division. In the process, about 20-40% of the potential value is typically left on the table. The discussion focuses on how to align objectives and achieve cooperation across divisions. It turns out that such cooperation is hard to achieve in a competitive culture. How, then, can the firm create a cooperative culture? This, it turns out, may be a VRIO resource… The “Vision Thing” exercise is designed to help students distinguish the activities of leaders and managers in a fun and engaging manner. The exercise involves creating a three-tiered hierarchical structure. One person is the CEO, another is the manager, and a third is the employee. The CEO prepares a vision statement in advance and works with the manager to determine how to translate the vision to a tangible “product” using the toy construction set. The manager then guides the employee on building the “product.” The process is iterative in nature—the manager can communicate with the CEO and employee as often as necessary. But there is a finite amount of time available to implement the vision. Once the exercise is complete the team comes together to examine how close the team came to implementing the CEO’s vision. The learning objectives are:

The “Vision Thing” exercise is designed to help students distinguish the activities of leaders and managers in a fun and engaging manner. The exercise involves creating a three-tiered hierarchical structure. One person is the CEO, another is the manager, and a third is the employee. The CEO prepares a vision statement in advance and works with the manager to determine how to translate the vision to a tangible “product” using the toy construction set. The manager then guides the employee on building the “product.” The process is iterative in nature—the manager can communicate with the CEO and employee as often as necessary. But there is a finite amount of time available to implement the vision. Once the exercise is complete the team comes together to examine how close the team came to implementing the CEO’s vision. The learning objectives are: Rich Makadok invites his students to send pictures of strange business combinations. The sequence of

Rich Makadok invites his students to send pictures of strange business combinations. The sequence of