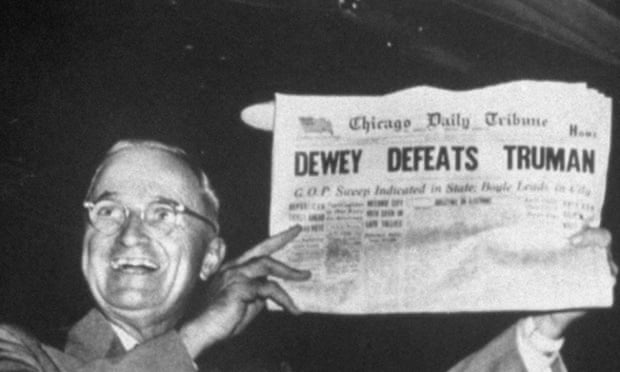

This isn’t the first time polls have been wrong. The election of Donald Trump was a shock to many college students (as well as the press) and this may warrant some class time. Some instructors responded by providing space for students to express their feelings and this may be within the scope of the educational objectives for some classes. For a strategy class, a more relevant focus might be to examine the implications of the outcome for business strategies or to examine the campaigns from a strategic perspective. This might be considered as a template for how to discuss other sudden world events in the strategy classroom. Here are some takes on how to bring the election in while still emphasizing the pedagogical objectives of a strategy course:

This isn’t the first time polls have been wrong. The election of Donald Trump was a shock to many college students (as well as the press) and this may warrant some class time. Some instructors responded by providing space for students to express their feelings and this may be within the scope of the educational objectives for some classes. For a strategy class, a more relevant focus might be to examine the implications of the outcome for business strategies or to examine the campaigns from a strategic perspective. This might be considered as a template for how to discuss other sudden world events in the strategy classroom. Here are some takes on how to bring the election in while still emphasizing the pedagogical objectives of a strategy course:

- Project case scenario analyses (Aya Chacar). Scenario analysis is designed to unearth factors that affect the efficacy of a given strategy. In a global context, country risk is a central factor in assessing strategic alternatives. In class, students discussed the likely impact of the election on the companies their teams are studying. Can you help the company? What do you think “could” be the impact on the companies under the new American administration -based on stated positions or past behavior? The companies they chose to study in this class are Amazon, Auchan, Didi Chuxing, General Motors, Naver, Uber, Volkswagen, and Walmart. All already have major international presence with some but not all having significant operations in China, Europe, India, Japan, Mexico, South Korea, SouthEast Asia and the US.

- Entrepreneurship/Opportunity Recognition. The pollsters were all wrong. Often businesses and whole industries miss critical trends in consumer preferences and this probably means that there is unserved market space. Given trends that are now unearthed by the election, what market opportunities might there be for firms in various industries? One could use the project firms, cases you have done or specific firms that you think might be affected.

- SWOT on campaigns (Peter Klein). While this framework is not preferred by most strategy scholars, it may raise some good points. A few examples from the Clinton campaign: O: demographics (e.g., increased Hispanic population, more socially tolerant electorate), unpopular opponent,chance to make history. T: middle-class concerns about economic inequality, backlash against political correctness, Clinton fatigue, incumbent fatigue, WikiLeaks. S: experience; support from major media, Wall Street, large corporations; ties to Obama and WJ Clinton; large staff of handlers; polish. W: experience; support from major media, Wall Street, large corporations; ties to Obama and WJ Clinton; large staff of handlers; polish.

- Resources/Capabilities. Many of the campaign strengths turn out to be weaknesses depending on the context (experience, polish, support from corporations, etc.). What resources give a party a sustained advantage? What does “sustained” mean in this context? This might bring in a discussion of core rigidities and how once valuable resources can become critical weaknesses over time.

- Disruptive Innovation (David Burkus). Clay Christensen described disruptive innovations as an innovation (typically from an outsider) that creates a new market and value network that eventually disrupts an existing market and value network, displacing established market leading firms, products and alliances. The Trump campaign might be viewed in this light as a disruptive strategy that overtook the conventional establishment.

- PESTEL. Of course, this demonstrates the value/importance of looking outside of the industry for trends that may influence whether a given strategy will be effective or not. The PESTEL framework is a simple tool for bringing this in to the analysis (Political, Economic, Social Technological, Environmental, and Legal).

- First 100 Days. Trump offered an ambitious list of things he planned to try and accomplish in the first 100 days. One can divide the list among groups and ask them to identify the implications of the policies for business in general or, preferably, for a specific firm/client.

Contributed by Russ Coff

Most students quickly grasp the concept of game theory–figuring out what your opponent is likely to do helps you decide what you ought to do. As this clip shows, however, failing to understand the real decision choices to be made can lead to deadly, but funny results. In class, after introducing simultaneous vs. sequential games, I show the clip, pausing it just before the 2:11 mark. At this point the poison is in the goblet, and I ask the students who haven’t seen the movie which goblet they think is poisoned. I record answers, and then show the clip (up to anywhere between 4:45 and 5:02). I then ask if they were surprised. I then show the remainder of the clip, and we discuss what mistake Vazinni made. Students see the real payoff matrix as: a) if I (Vazinni) guess wrong, I’m dead; b) If I guess right, then the Dread Pirate Roberts knows it too has incentive to kill me before he dies. I only live if Iocane powder kills instantly. My correct answer can only be not to drink either goblet if I want to live. After watching this video clip and class discussion, students can:

Most students quickly grasp the concept of game theory–figuring out what your opponent is likely to do helps you decide what you ought to do. As this clip shows, however, failing to understand the real decision choices to be made can lead to deadly, but funny results. In class, after introducing simultaneous vs. sequential games, I show the clip, pausing it just before the 2:11 mark. At this point the poison is in the goblet, and I ask the students who haven’t seen the movie which goblet they think is poisoned. I record answers, and then show the clip (up to anywhere between 4:45 and 5:02). I then ask if they were surprised. I then show the remainder of the clip, and we discuss what mistake Vazinni made. Students see the real payoff matrix as: a) if I (Vazinni) guess wrong, I’m dead; b) If I guess right, then the Dread Pirate Roberts knows it too has incentive to kill me before he dies. I only live if Iocane powder kills instantly. My correct answer can only be not to drink either goblet if I want to live. After watching this video clip and class discussion, students can: Economics-games.com

Economics-games.com

Ive “worked closely with the late co-founder Steve Jobs, who called Mr Ive his spiritual partner on products stretching back to the iMac.” As before, the reliance on a single person in this role raises key questions: An article published in the New Yorker earlier this year described how “Mr Ive had been describing himself as both ‘deeply, deeply tired‘ and ‘always anxious’ and said he was uncomfortable knowing that ‘a hundred thousand Apple employees rely on his decision-making – his taste – and that a sudden announcement of his retirement would ambush Apple shareholders.‘” Can this be described as an organizational capability? An organizational routine? A dynamic capability? Does it matter that the capability is largely embedded in a single person who is not an owner? All good questions to kick off a nice class discussion…

Ive “worked closely with the late co-founder Steve Jobs, who called Mr Ive his spiritual partner on products stretching back to the iMac.” As before, the reliance on a single person in this role raises key questions: An article published in the New Yorker earlier this year described how “Mr Ive had been describing himself as both ‘deeply, deeply tired‘ and ‘always anxious’ and said he was uncomfortable knowing that ‘a hundred thousand Apple employees rely on his decision-making – his taste – and that a sudden announcement of his retirement would ambush Apple shareholders.‘” Can this be described as an organizational capability? An organizational routine? A dynamic capability? Does it matter that the capability is largely embedded in a single person who is not an owner? All good questions to kick off a nice class discussion… Here is a simple exercise to demonstrate competitive advantage on the first day of class. Hold up a crisp $20 bill and ask “Who wants this?” When people look puzzled, ask, “I mean, who really wants this?” and then “Does anyone want this?” Continue this way (repeating this in different ways) until someone actually gets up, walks over, and takes the $20 from your hand. Then the discussion focuses on why this particular person got the money. How did their motivation differ? Did they have different information or perception of the opportunity? Did they have a positional advantage based on where they were sitting? Other personal attributes (e.g., entrepreneurial)? The main question, then, is why do some people/firms perform better than others? This simple exercise gets at the nexus of perceived opportunity, position, resources, and other factors that operate both at the individual and firm level. Note that instructors should tell the class not to share this with other students. However, if you do have a student who has heard about the exercise (and grabs the money), asymmetric information about an opportunity is certainly one aspect of the discussion. The following “

Here is a simple exercise to demonstrate competitive advantage on the first day of class. Hold up a crisp $20 bill and ask “Who wants this?” When people look puzzled, ask, “I mean, who really wants this?” and then “Does anyone want this?” Continue this way (repeating this in different ways) until someone actually gets up, walks over, and takes the $20 from your hand. Then the discussion focuses on why this particular person got the money. How did their motivation differ? Did they have different information or perception of the opportunity? Did they have a positional advantage based on where they were sitting? Other personal attributes (e.g., entrepreneurial)? The main question, then, is why do some people/firms perform better than others? This simple exercise gets at the nexus of perceived opportunity, position, resources, and other factors that operate both at the individual and firm level. Note that instructors should tell the class not to share this with other students. However, if you do have a student who has heard about the exercise (and grabs the money), asymmetric information about an opportunity is certainly one aspect of the discussion. The following “ Economic bubbles reflect irrational escalation but there is always an element of underlying rationality. This classic exercise,

Economic bubbles reflect irrational escalation but there is always an element of underlying rationality. This classic exercise,  Abercrombie & Fitch is struggling (

Abercrombie & Fitch is struggling ( The near field communications (NFC) technologies that they rely on require that merchants invest in new technology at the point of sale. Samsung has acquired

The near field communications (NFC) technologies that they rely on require that merchants invest in new technology at the point of sale. Samsung has acquired  An emerging literature focuses on learning from failures — both in terms of entrepreneurship and strategy more broadly. For some recent examples, see studies by

An emerging literature focuses on learning from failures — both in terms of entrepreneurship and strategy more broadly. For some recent examples, see studies by