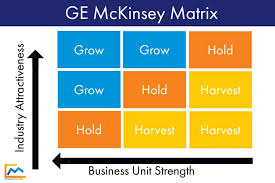

The GE/McKinsey matrix is a classic strategy framework … gone bad. Initially thought to be a radical innovation, it guided flawed corporate diversification strategies of the 1980s. Indeed, it is still sometimes taught in business schools, and some consultants still sell this analysis as a service. My first intuition is to ignore it in class. Indeed, I’ve not discussed this framework in class since posting a collection of exercises from the late 1990s here where the data reflected the Sears Financial Network.

However, showing the framework’s flaws can help students to see what they should be looking for when analyzing diversification strategies. Brian Silverman suggested that we update the exercise so students would evaluate a disguised version of Disney’s portfolio using the tool. Without context, the studio and video game divisions appear to be “dogs” to be divested, and the theme parks seem to be stars. The relationship between the units is opaque. Once the company and divisions are revealed, it becomes apparent that the links between businesses are absolutely critical. Of course, the theme parks are especially valuable because they can leverage creative output from the studios.

Since my class is partially online, I created this Google sheet to facilitate the exercise that will accommodate up to 12 student teams. It would also prove useful in a large in-person class. Here’s how it works:

Continue reading

Team projects are quite common in strategy classes. While the topic of team effectiveness is usually more central for organizational behavior courses, it is essential for organizational effectiveness … and team projects. While you may not want to allocate a lot of time and resources to the topic, you may want to get teams off to a good start so you don’t have to address dysfunctions later in the semester. One reason things may go south is the team’s desire for a “fast and enthusiastic start.” A bias for action can sometimes sabotage collaborative efforts. That well-meaning call to action — “let’s get this done!” – can result in a “sloppy start.”

Team projects are quite common in strategy classes. While the topic of team effectiveness is usually more central for organizational behavior courses, it is essential for organizational effectiveness … and team projects. While you may not want to allocate a lot of time and resources to the topic, you may want to get teams off to a good start so you don’t have to address dysfunctions later in the semester. One reason things may go south is the team’s desire for a “fast and enthusiastic start.” A bias for action can sometimes sabotage collaborative efforts. That well-meaning call to action — “let’s get this done!” – can result in a “sloppy start.” Class participation is typically a major component of grades in strategy courses. Some students are quite comfortable participating. Others not so much. This video from

Class participation is typically a major component of grades in strategy courses. Some students are quite comfortable participating. Others not so much. This video from  Strategy classes often give short shrift to managing change but this is where the rubber hits the road.

Strategy classes often give short shrift to managing change but this is where the rubber hits the road.  Generic strategies are easy enough to explain and students typically feel that they understand. But do they really? Could they develop and implement a sound strategy? Sometimes it’s worth a bit of additional hands-on experience to make sure the lessons stick. Probably the most important message is alignment — the need to design the organization and product to fit the strategy. In other words, to make the appropriate tradeoffs.

Generic strategies are easy enough to explain and students typically feel that they understand. But do they really? Could they develop and implement a sound strategy? Sometimes it’s worth a bit of additional hands-on experience to make sure the lessons stick. Probably the most important message is alignment — the need to design the organization and product to fit the strategy. In other words, to make the appropriate tradeoffs.  Entrepreneurship students often think they’ve found a “no brainer” idea – one that everyone “obviously” will want. We’ve all seen it before – an idea that is so good that it requires zero dollars for customer acquisition because word of mouth and social media will lead to infinite sales, virtually overnight.

Entrepreneurship students often think they’ve found a “no brainer” idea – one that everyone “obviously” will want. We’ve all seen it before – an idea that is so good that it requires zero dollars for customer acquisition because word of mouth and social media will lead to infinite sales, virtually overnight. When leading a case discussion, wouldn’t it be nice to know exactly what positions students were prepared to defend? You want to bring people into the conversation who you know will have diverse perspectives to bring about a balanced discussion.

When leading a case discussion, wouldn’t it be nice to know exactly what positions students were prepared to defend? You want to bring people into the conversation who you know will have diverse perspectives to bring about a balanced discussion.  A related innovation is tents that display the letters A through D. This can be used for cases that offer up to 5 alternatives that students might vote for (a,b,c,d, and no tent).

A related innovation is tents that display the letters A through D. This can be used for cases that offer up to 5 alternatives that students might vote for (a,b,c,d, and no tent).  With its $13.7B bid, Amazon agreed to pay a 27% premium over Whole Foods’ previous market valuation. This makes for a nice live case case in your strategy classroom. Was this a sound business decision? The market rewarded Amazon with an increase in its stock price. While some opportunities are apparent, it remains unclear exactly how Whole Foods will be worth 27% more to Amazon (and that’s just to break even). A five forces analysis will reveal that the grocery market is highly competitive with exceptionally thin margins — not an especially attractive industry to enter. So how can they win in this game? There are many possibilities that may come up in a discussion. For example, Amazon may:

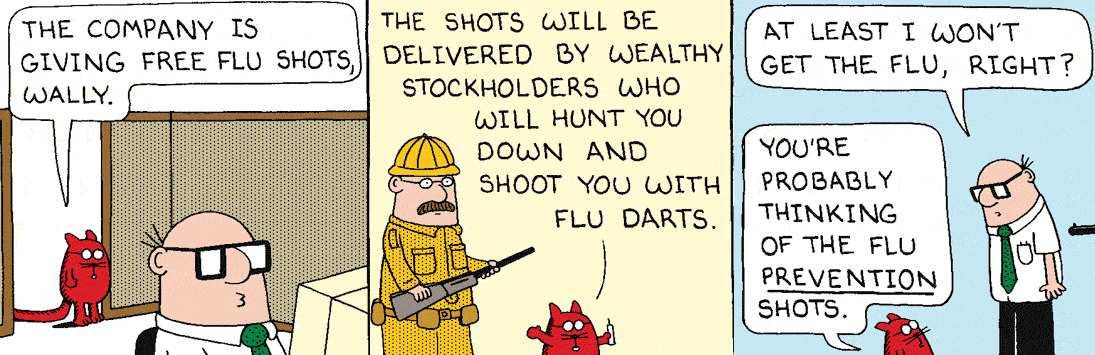

With its $13.7B bid, Amazon agreed to pay a 27% premium over Whole Foods’ previous market valuation. This makes for a nice live case case in your strategy classroom. Was this a sound business decision? The market rewarded Amazon with an increase in its stock price. While some opportunities are apparent, it remains unclear exactly how Whole Foods will be worth 27% more to Amazon (and that’s just to break even). A five forces analysis will reveal that the grocery market is highly competitive with exceptionally thin margins — not an especially attractive industry to enter. So how can they win in this game? There are many possibilities that may come up in a discussion. For example, Amazon may: Strategies rarely work out as planned but somehow, students remain eternally hopeful that everything will go exactly as they expect. This experiential exercise allows students to “feel”

Strategies rarely work out as planned but somehow, students remain eternally hopeful that everything will go exactly as they expect. This experiential exercise allows students to “feel”  Inflate ball & sit on it. Ask 2 volunteers to inflate a heavy duty inflatable ball using a small air pump (one can buy these a sport store) and try to sit on it afterwards for a minute. While introducing the exercise, the instructor should keep the plug hidden in her/his pocket. Inflating the ball is amusing (both the volunteers and the audience). It is not easy or quick to inflate the ball.

Inflate ball & sit on it. Ask 2 volunteers to inflate a heavy duty inflatable ball using a small air pump (one can buy these a sport store) and try to sit on it afterwards for a minute. While introducing the exercise, the instructor should keep the plug hidden in her/his pocket. Inflating the ball is amusing (both the volunteers and the audience). It is not easy or quick to inflate the ball. takes the plug out admitting that she/he had it all the time. The class will laugh. It may be frustrating for the volunteers but then we begin the debrief and explain the reason for the deception in the exercise.

takes the plug out admitting that she/he had it all the time. The class will laugh. It may be frustrating for the volunteers but then we begin the debrief and explain the reason for the deception in the exercise. This is another in our series of explorations in

This is another in our series of explorations in

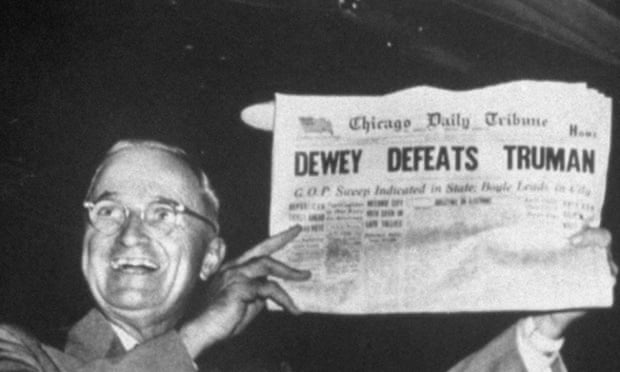

This isn’t the first time polls have been wrong. The election of Donald Trump was a shock to many college students (as well as the press) and this may warrant some class time. Some instructors responded by

This isn’t the first time polls have been wrong. The election of Donald Trump was a shock to many college students (as well as the press) and this may warrant some class time. Some instructors responded by  What follows is a brief description/outline of the lecture. While it certainly won’t do it justice, it may offer some important ideas for instructors to explore.

What follows is a brief description/outline of the lecture. While it certainly won’t do it justice, it may offer some important ideas for instructors to explore. Managing change is given little time in most strategy courses. We often understate how difficult strategic change actually is and then wonder why organizations struggle so much with implementation (and our students think its all common sense). You can think of it as walking blindfolded on a tightrope between two solid foundations. During the transition, there is great uncertainty about whether the desired path is attainable. This, of course, is another way of looking at Lewin’s unfreeze/change/refreeze model. This video can help to illustrate the issue:

Managing change is given little time in most strategy courses. We often understate how difficult strategic change actually is and then wonder why organizations struggle so much with implementation (and our students think its all common sense). You can think of it as walking blindfolded on a tightrope between two solid foundations. During the transition, there is great uncertainty about whether the desired path is attainable. This, of course, is another way of looking at Lewin’s unfreeze/change/refreeze model. This video can help to illustrate the issue: Economics-games.com

Economics-games.com